![]()

Beyond Memes

Beyond Memes

Memes and genes have much in common. Both are selfish in that each "wants" itself replicated.

As memes develop in human culture, itself a product of mind, they carry only information, which requires consciousness to convey them for further replication. In themselves, memes are part of a blind force.

As with genes, successful memes beat the competition. They get copied. In a day we meet countless numbers of them, words on a Wheaties box, songs on the car radio, news on television. Remembering maybe less than five percent of a day's experiences, we see or hear Tony Blair, George Bush, John Kerry, Martha Stewart, Big Bird, Mickey Mouse, Teletubbies, Jay Leno, Fords, Chevies, Jaguars, Toyotas, Oscar Mayer weiners, Heinz Catsup, Starbucks Coffee, Bach fugues, Beethoven sonatas, Justin Timberlake, Janet Jackson, Dixie Chicks, McDonalds, email messages, newspaper captions, street posters, the family dog.

Consciously or subconsciously, those that get remembered have a chance for survival. Others eventually die, their only hope dwindling as fewer and fewer leap from human brain to human brain.

Poets once wrote of the good, the true, and the beautiful as that which is worthy of survival. Although it can be, this is not necessarily the case with memes. Think of them as viruses.

Viruses, either biological or computer, seek a host. Memes, then, can be a kind of parasite in that they "piggy back" until one brain passes them on to another.

Sometimes they survive best in groups of memes.

Richard Dawkins uses Roman Catholicism as an example of meme groups. By this group, the religion grows. Memes are church teachings, including the catechism and prayer. During mass one sings hymns. Worshippers feel nearer to God as they walk into a catheral with high, vaulted ceilings, the organ music resonating off stained glass windows. These become part of memetic gospel, to have many children so that the faith can be passed on generation to generation. Of course, the pinnacle meme is the promise of everlasting life or its counterpart, fear of eternal damnation. Attendant upon this group is faith in Church dogma and doctrine. God's invisibility is also part of the meme group. Observing people, He notices their deeds and numbers their days. This meme group has been remarkably successful, surviving and prospering for hundreds of years.

Memes arise in the mind without invitation. They come and go. A tune may haunt somebody for days, its lyrics or melody returning each morning until it wears away and something replaces it. Often planted by society, culture, or religion, they shape entire peoples and dominate lives. They offer no escape from themselves and whole populations become their willing servants.

Such a meme in the United States is individualism. It evolved out of American history and the struggle to tame the land. Settlers, pioneers, and immigrants of all kinds found themselves in the wilderness without societal resources and dependent only on their own grit. Neighbors lived on the other side of the mountain, in the next valley, down river. When a Nebraska sod farmer saw chimney smoke on the horizon he might pack up his family and move further west because he disliked civilization's encroachment. (Also see

Mother Cultures: Individualist and Collectivist, 19 January 2004 at a companion site.)

Today in the United States, people remain steeped in the myth of individualism, a kind of tough self-responsibility, to the neglect of the ties that bind. Unlike Europeans, Americans think less of their mutal interdependence and more of their own responsibility to make it in the world. This has fostered great respect for the self-made, the billionaires who command corporate empires, but it has blinded them to their need for one another, thereby affecting social institutions.

As for memes, they continue to arise as unbidden viruses, our minds hosting them. They are welcome guests for minds, although some people know them for their true nature. Memes reveal to us that, for the most part, we don't think. Instead, we are thought. We have no understanding unless we recognize memes for what they are.

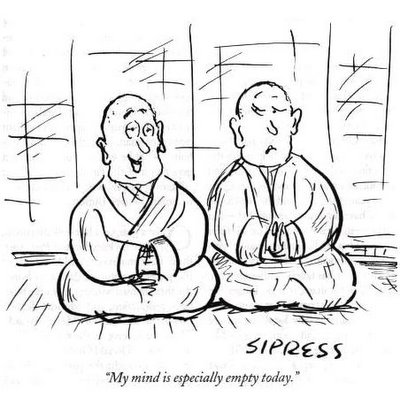

To do this, consciousness must empty itself. Meditation allows one approach; another depends on dwelling upstream from where memes enter. The first, is done by sitting, say, in Buddhist Zazen; the second, by turning the "flashlight" of consciousness on thoughts. Either approach requires months, or years, perhaps decades, of application. Eventually, the investigator may discover that mind itself is the meme of memes, the matrix that sustains them, and is as illusory as they are.

Meme theorists such as Dawkins and Dennett will continue to manufacture memes disguised as theories about mind, and well they should, for their reasoning has promoted new ways to think about mind. But unless they steadfastly apply themselves to methods known in the East for centuries, they will never really know whereof they speak. Given the tenor of their thought, they might regard "beyond memes" as naive intuition, unsupportable by sophisticated inquiry, but they have achieved no breakthroughs in consciousness study. Instead they ingeniously marshal evidence in new ways. Only investigation into the "beyond meme" concept would allow understanding, not labels. Intellectual work on consciousness is absolutely necessary but much of it misses the point because thinkers and researchers think about it rather than direct attention to experiencing it. Let them get away on a Zen retreat, or put them somewhere in solitude for extended periods, and always with their resolve to pay attention to what happens.

(Also see

Enlightenment Gene, 3 March,

Memes and Why Evolution Favored The Irrational Brain 26 February,

Memes, Genes, and God, 31 December.) Thorstein Veblen in

The Theory of The Leisure Class wrote about memes

without having a name for them.

Read him on Dogs as a meme 27 May 2004.

In Japanese commercial hatcheries when chicks are born, trained sex spotters divide them into males and females. This is known as chicken sexing. The divided groups are treated differently. The females are fed because they will produce eggs; a few males are fattened for meat while the rest are deemed useless and early on meet a fate later encountered by all animals in a factory system.

In Japanese commercial hatcheries when chicks are born, trained sex spotters divide them into males and females. This is known as chicken sexing. The divided groups are treated differently. The females are fed because they will produce eggs; a few males are fattened for meat while the rest are deemed useless and early on meet a fate later encountered by all animals in a factory system.