AddThis

Showing posts with label Brain In A Vat. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Brain In A Vat. Show all posts

4/28/11

Lawrence Shapiro On Embodied Cognition: No Brain In A Vat Here

What is embodied cognition? A view in which cognition isn't from the brain alone, but which involves the brain, the body, and the environment. If you check the dictionary, you will find that cognition is described, in short, as using our minds in interaction with things to acquire knowledge and understanding. We think, we experience, we sense these things.

A philosopher of mind, Rolf Pfeifer has written a book on embodied cognition, titled How the Body Shapes the Way We Think. Others interested in embodied cognition include Alva Noë. Mind Shadows has an article on him here.

In an interview with Ginger Campbell, Shapiro observes that regarding the brain as intermediary between "inside" and "outside"--my terms, not his--tempts us to believe that the brain's function is isolated from the body's.

3/8/04

A Thought Experiment: Where Are You?

A Thought Experiment: Where Are You?

Where are you? Most people say that they are behind the eyes. Blind people often feel themselves at their finger tips when reading Braille, or at the handle of their cane when walking. Sometimes people feel themselves at the edge of a car as they almost have an accident with a passing vehicle.

But where are you? Plausibly, scientifically, you reside in your central nervous system, your brain. Electrodes attached to its different areas can stimulate various memories, feelings, and movements.

The question remains, though.

As part of a thought experiment originally proposed by Daniel Dennett, assume that your brain has been removed from your skull and placed in a vat of chemicals that nurture it. Your body has total, unimpaired ability to move about, although minus your brain. Instead, in your cranium is a transmitter that sends sights, sounds, touches, and scents, back to the brain. While your body roams freely, your brain remains in the vat, experiencing whatever the body encounters.

Where would you locate yourself? Most people would say they would believe themselves not in the vat but wherever their body goes. They would still feel that they lived somewhere behind the eyes. Only a transmitter is located there.*

So where, then, is the self, this seemingly basic element that everybody senses as present, and discusses as if it is real? What about all the words referring to it--I, you, him, or her? Apparently, because the self cannot be located, they belong to the metaphysics of grammar. (See The Metaphysics of Grammar, 17 January 2004.)

We feel that we are a central observer, but wherever we look we don't find him or her. We are the teller of our tale. We have a narrator, so we believe, and this narration shapes our lives. Where is the narrator?

If we cannot find the teller, then what about the tale? We have memories and hopes. We locate ourselves in space and time. Still, without a teller, where is the tale? (See Perception, 8 December 2003.)

In quantum physics, evidence mounts to indicate that consciousness is non-local. This would not surprise a Ramana Maharshi or a Dogen Zenzi. (For an article on non-local consciousness, see John Bell's Inequality Theorem and Alain Aspect's experiments, in Looking For Reality, 10 November 2003.)

Even non-local consciousness does not fully explain the fact that whenever we look for the self we cannot find it.

For further discussion of the elusive self, see Shakey, Beavers, and Cartesian Theater, 12 February 2004, Cartesian Anxiety, Francisco Varela and The Emergent Self, 6 January 2004 and Benjamin Libet's experiments in Looking for Self, 8 November 2003, as well as various other articles at this site.

For another brain/vat thought experiment, see Brain In A Vat, a different proposal, 20 November 2003.

* (Is this similar to the phantom limb syndrome, in which one feels a foot itching even though the leg was amputated?)

1/23/04

Roger Penrose, Consciousness, and Wave Function Collapse

Roger Penrose, Consciousness, and Wave Function Collapse

Our everyday world of classical physics makes sense. If we drop a pebble in a pond it causes waves and sinks to the bottom. At the quantum level the pebble itself would not only initiate the action, but would become a wave. What happens at the borderland between classical physics and quantum physics? Why can we not connect the two in our understanding? On the one hand, we have a ball going where we toss it. On the other, we have balls "tossing" everywhere at once at the quantum level. Is something missing in the way we think?

Some physicists don't like such questions and prefer established investigation patterns, world paradigms which allow acceptable communication between community members. The eminent physicist and mathematician Roger Penrose is asking questions that are on the fringe. He says something is being overlooked in physics. We need a new way of understanding how the mind works. He lays out his ideas in Shadows of The Mind.

Artificial intelligence, or computing, is a current model for thinking about consciousness. Penrose regards it as inappropriate. Using Kurt Gödel's Incompleteness Theorem, he argues that computational models of intelligence are inadequate to understand mind. Physics itself, says Penrose, is noncomputable. Even the most mathematically inclined people spend far less time than computers do in crunching numbers. Indeed, most of their insight come in leaps of intuition. With Gödel's Incompleteness Theorem, Penrose argues that Alan Turing's Intelligence Machine* cannot do what people can. Computers will not know when to stop computing a noncomputable operation. The human mind will recognize when to stop. Penrose points out that a computer will continue its operations searching for an answer to Gödel's Theorem.

* ( Is this human/artificial intelligence test empirically irrelevant? That is, does it belong in the same category as Zeno's Paradox, which is empirically irrelevant? (See Brain in A Vat and Peter Lynds.) We know that despite what Zeno demonstrated, people in fact do reach end points. We also know that despite artificial intelligence theorists' arguments, machines do not demonstrate love, compassion, intuition, or longings for God, mystery, and deceased kin.)

Kurt Gödel aside, the big problem is wave function collapse, which occurs when a quantum event is measured. Penrose posits that the human mind itself is subject to wave function collapse and supposes that brain microtubules allow it. Microtubules are tiny enough to fit at the quantum level while neurons belong at the classical physics level. Within neurons, cytoskeletons form the structures that are the "glue" for cells. Inside them are microtubules, only 25 nanometers in diameter, which control synapse function.

In an interplay between the quantum cytoskeletal state and classical neurons, consciousness is manifested: anesthesiologist Stuart Hameroff's findings support part of this description, but not Penrose's interpretation of it--that consciousness is manifested in the interplay.

When a human makes a quantum observation, wave function collapse occurs. Penrose assumes it results from human consciousness. Until the observation, the quanta are in a superposition of all possible states. (See Schrödinger's Cat, 2 January) Observation causes the quantum system to reduce (collapse) to a specific state.

Penrose argues that a corresponding collapse occurs in consciousness, and within certain microtubules. They self-collapse and each time they do, they correspond with a discrete consciousness event. Sequences of these events give rise to our sense of time,** and a stream of consciousness. Unlike computers, this collapse is non-algorithmic and is what separates us from machines. **(See Peter Lynds, Einstein, Time and "block" universe, 20 November--time as points rather than flow)

Perhaps most outrageous to the scientific community is that Penrose is led to believe in a Platonic scenario. With Plato, for every chair we sit on, its ideal counterpart exists metaphysically as a Platonic form.* For Penrose, conscious states exist in a world of their own, which our minds access. Unlike Plato, his world is physics rather than metaphysics. (Some of his opponents doubt this :-) *(See Julian Barbour here, here, and here.)

With the correspondence between wave function collapse in mind and the objects of mental observation, he seeks to rescue the world of macrophysics (in some instances like the common sense world we experience) and make it compatible with quantum physics. Einstein's gravitational world up to now has been undermined by Superposition Theory (See Schrödinger's Cat, 2 January). Penrose wants to resolve quantum paradoxes to make them "fit" with Einstein's view. He argues that it makes no sense to use the term "reality" for only objects we can see.

Penrose has enough stature that he can risk his reputation on this book, which many consider as wild-speculation. He follows a long line of risk takers, including Copernicus and Darwin. He has stirred up debate, which is good. This could also be science's future. In his last sentence, he says, "These are deep issues, and we are very far from explanations. I would argue that no clear answers will come forward unless the interrelating features of all these worlds [mental, physical, Platonic/mathematical] are seen to come into play. No one of these issues will be resolved in isolation from the others. I have referred to three worlds and the mysteries that relate one to another. No doubt there are not really three worlds but one, the true nature of which we do not even glimpse at present."

(Also see John Wheeler and delayed choice.)

11/20/03

Brain in A Vat

Brain in A Vat

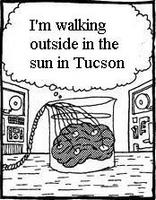

Assume that a brain could live in a vat of chemicals and, wired by external electrodes, it would have all the normal experiences: childhood, sex, falling in love, parenting, even skiing, or sky diving. It imagines itself a person capable of a full range of activity. It has beliefs: it is a person with a name, say, Harvey Smedlap; it has a family; it enjoys food; it has orgasms; a god created it and protects it. It regards all this evidence as reliable.

Now, a question: how can one differentiate his own beliefs from that of the brain in the vat? How can one say that his evidence is more reliable than that of the brain?

Labels:

Brain In A Vat

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)