Mention Elly Beinhorn to somebody today and he or she will look at you blankly.

Not so, in the era between World Wars One and Two. During the twenties and thirties, hers was a household name on many continents. She was an aviatrix, a daring young woman in the mold of Amelia Earhart. Like other such women of her time, her goals were not properly feminine. Yet as she became famous, people said her flying skills were exceeded only by her femininity. That was it, a most unwomanly thing. She wanted to fly an aeroplane around the world. Alone. Her mother wept and her father threatened to send her to a psychiatrist, but an aunt had died and left Elly a little money.

It all began when friends took her along to a lecture by a well-known German pilot Hauptmann Hermann Kohl, who had just flown the Atlantic.

Born in Hannover, Germany in 1907, at 21, Elly thought if a man could do that so could she. Taking a small Berlin flat she took flying lessons and soloed just before her money ran out. Her instructor suggested she get an aerobatic license and stunt fly. Soon she was making good money at air shows all over Germany each weekend. This was 1929.

WWI was over. Germany was in deep depression. A wheelbarrow of marks couldn't buy a pack of cigarettes, wrote Ernest Hemingway as foreign correspondent. Elly saw all of this, but she was young, and her eyes were on the horizon, not on Germany.

As Hitler gathered power, she embarked on a global adventure. With photo-journalism contracts from several publications, she flew a scientific expedition to West Africa. All went well until flying solo over the Sahara when she suffered engine failure and landed in the middle of the desert.

She sighted several searching planes, which couldn't see her. After several days a few Tauregs came upon her, and examined the strange thing, a plane, a creature seemingly fallen from the sky. Lepers, they were outcast from their tribe, but helped her find a caravan, where she hitched a ride on a camel to that remotest of outposts, Timbuktu.

She did continue her journey, but that is a far longer story. She married famous German motorcycle and race car driver Bernd Rosemeyer in the 1930s. In order to have a competition license, he had to belong to the Storm Troopers, or SA. As a top driver for Auto Union, he was required by Heinrich Himmler to also belong to the SS, although he never wore the uniform. He was killed in 1938 on the Frankfurt-Darmstadt autobahn, built by Hitler for his Third Reich. That stretch of the bahn is one I often traveled when living in Germany. On the southbound side and where he crashed, it had a monument with plaque in memory of Rosemeyer.

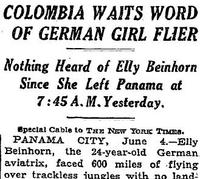

As to her global flight, here is a clipping from the New York Times, June 5, 1932:

In 1937 she flew across the United States and became good friends with Amelia Earhart. In 1959 she accepted an invitation to take part in the Powder Puff Derby in the States. At the Derby she learned from The Ninety-Nines, otherwise known as International Organization of Women Pilots, that they wanted to produce an Amelia Earhart stamp. But the production had been held up due to insufficient funding. Recalling deposits she and Bernd Rosemeyer had made twenty years before in an American bank, Elly contacted the bank to find that the amount had accumulated considerable interest. She gladly contributed the money toward a stamp in memory of her friend Amelia.

In 1937 she flew across the United States and became good friends with Amelia Earhart. In 1959 she accepted an invitation to take part in the Powder Puff Derby in the States. At the Derby she learned from The Ninety-Nines, otherwise known as International Organization of Women Pilots, that they wanted to produce an Amelia Earhart stamp. But the production had been held up due to insufficient funding. Recalling deposits she and Bernd Rosemeyer had made twenty years before in an American bank, Elly contacted the bank to find that the amount had accumulated considerable interest. She gladly contributed the money toward a stamp in memory of her friend Amelia. Here is a picture of her in March 30, 2003, on her 96th birthday, snow white hair, the very model of a well-coiffed lady. She is sitting in an up-scale German retirement home for an interview with a journalist.

Here is a picture of her in March 30, 2003, on her 96th birthday, snow white hair, the very model of a well-coiffed lady. She is sitting in an up-scale German retirement home for an interview with a journalist.Her son, also named Bernd Rosemeyer, is a prominent German orthopedist, who appears in a family photo taken January 25, 1938, when he was a ten week-old baby, held in the arms of his father. The elder Rosemeyer was killed three days later on the Frankfurt-Darmstadt autobahn. Her son facilitates the interview. He says, “Hallo. Mom. How do you feel today? Good? Good. We have visitors.”

The interviewer describes her as having light blue eyes. He thinks of her as a pilot who must make split-second decisions. "She has seen, checked, validated, and acquired us: she is again mastering the scenario, ready to cope with the expected and the unexpected."

Later in the interview, Bernd asks about a photo of her next an airplane. The old mastery, unfortunately, has gone. The account goes like this.

"What make of plane is that?"

"A Klemm," she replies.

It is not. Fuselage lettering reveals it as Heinkel. Bernd tells her so.

"No, I've never flown Heinkels," she says.

During the interview she recalls that in the days she flew into Africa, across other continents, and over oceans, she had no radio and could rely only on compass, experience, and the seat of her pants, the sensation most trusted by pilots of her era.

She recalls so many names, names unknown or forgotten today.

Professor Eberan-Eberhorst, technical director of race car development, Auto Union.

Professor Ferdinand Porsch, inventor of Hitler’s Volkswagen, or People’s Car, and the fancier one, the sleek vehicle that is his namesake.

She mentions many others. Among those she doesn't mention is Richard Halliburton, also long forgotten. He was a celebrated travel writer and adventurer of the same era, who was lost at sea on a Chinese junk bound out of Hong Kong to the 1939 San Francisco World's fair. He and Moye Stephens also flew around the world and they crossed paths with her in India, Timbuktu, and elsewhere. He wrote an introduction to her book, Flying Girl. He said this about her: "Elly was an expert mechanic. . . Cylinders, spark-plugs, and piston rings were just so much knitting to her. She thought nothing of standing an entire day in her overalls, with monkey-wrench and oil can, dismembering engines. But when sundown came, she'd disappear for half an hour and emerge in evening dress, looking so lovely, so fragrant, so feminine, that Stephens and I were enchanted all over again each time.

A difference between Elli and Halliburton is that he died a bachelor in 1939, in a typhoon while sailing in a Chinese junk from Hong Kong for San Francisco; she lived long enough to tell her grandchildren many times about her feats of daring.

Elly died on November 28, 2007, at 100 years old in a home for the elderly near Munich, Germany. A German obituary stated that after the funeral service the family received condolences at Ottobrunn, near Munich. It explained that in 1936 she married Bernd Rosemeyer, the most successful Auto Union Grand Prix driver and that she would be buried next him the the Dahlem district of Berlin.

Don't Die in Bed: The Brief, Intense Life of Richard Halliburton covers Elly.