Space capsules, and Eastern I-told-you-so: or, Does a Bach Sonata Make Sound if Nobody Hears It?

Douglas R Hofstadter in Gödel, Escher, Bach, says this of a recording of Bach's Sonata in F minor, inspected by aliens outside the solar system after a space capsule lands on their planet: "Thus immediately its shape, acting as a trigger, has given them some information: that it is an artifact, perhaps an information-bearing artifact. This idea--communicated, or triggered, by the record itself--now creates a new context in which the record will henceforth be perceived. The next steps in the decoding might take considerably longer--but that is very hard for us to assess. We can imagine that if such a record had arrived on Earth in Bach's time, no one would have known what to make of it, and very likely it would not have gotten deciphered. But that does not diminish our conviction that the information was in principle there [my emphasis] ; we just know that human knowledge in those times was not very sophisticated with respect to the possibilities of storage, transformation, and revelation of information."

And so it is with all effort at ordering the world. We don't have Archimedes' lever, no standing point outside the world, or outside consciousness, from which we can speak with certainty. We can only say "it is our conviction," which carries a sense of reasonableness, but that's all it is. As I say in the 6 January article, "The traditional view of the world as external obscures or denies that we cannot explore or explain cognition without the very faculties we want to explore or explain. As living systems, we exhibit cognition. We occur within this circularity of X explaining itself."

Was the information already there? We are carried back to assumptions, not validations. (See When Is A Head Like A Rock?, 6 November.) Since the early decades of the last century physicists have found with the double slit experiment and wave/particle duality that whenever they try to validate, the wave function collapses so that they get a confirmation of sorts but not of a world wherein information is already there. Instead, information complies with the shape of their need for it. We think this occurs only on the quantum level, but how can we be sure that it does not also occur in our larger world and in the universe as gravitational?

Hofstadter supposes that rather than landing on a distant planet, the space capsule and its recording are met by a meteorite which, instead of deciphering the information, punctures it. We might be tempted to call the meteorite stupid, but "perhaps we would thereby do the meteorite a disservice. Perhaps it has a ' higher intelligence' which we in our Earth chauvinism cannot perceive, and its interaction with the record was a manifestation of higher intelligence. Perhaps, then, the record has a ' higher meaning'--totally different from that which we attribute to it: perhaps its intelligence depends on the type of intelligence perceiving it. Perhaps."

This fits with our modern situation in that we understand our intelligence to be limited either by consciousness alone or by a larger system of which we are unaware. Electrons seem to exist in various dimensions (not that we have ever seen them) and yet in our lives we apprehend only four dimensions--length, width, depth, and time. In wave mechanics, we get the information we are looking for. We get velocity if we measure one way, and position, if we measure another way. (See Heisenberg in the 10 November article.) To resolve our puzzlement we propose a Many Worlds theory to explain superpositioning (see Schrödinger's Cat, 2 January). Or we accept the standard Copenhangen Interpretation (See Wheeler, Delayed Choice, & Time, 21 September 2006.).

So Consciousness may indeed be all, and I have no doubt it is. But I don't regard this situation as leaving Eastern thinkers with an I-told-you-so smugness. They have wrapped their teachings in doctrine, dogma, and ignorance, and have remained satisfied with ancient explanations for the enlightenment experience. They project an aura of beatitude over somebody who has experienced it. Its initial stage, the discovery of no-self, need not be wrapped in some mystical ballyhoo, however liberating the revelation. Some modern scientists and philosophers of consciousness accept it as a given and have quite good and well-reasoned explanations for it. (Daniel Dennett is one; for a scientist's explanation at this site, see Varela: Cartesian Anxiety, 6 January.)

On the other hand, were more scientists to seek ways to render into theory the teachings of the ancient East, they might find practical explanations for that which has so far puzzled them at the quantum level. For example, an understanding of the manufacture of time by thoughts, would yield a new way of regarding the double slit experience. However, as I have pointed out elsewhere, this requires experiential expertise, and not just rational analysis *. (See Varela: Cartesian Anxiety, 6 January, and Dawkins, Memes, Genes, & God, 31 December.)

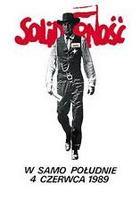

As for Bach's sonata and Hofstadter's space capsule, we allow them as hurtling somewhere through the black infinitude of space, although we cannot know where they are. What are they, if not a thought? To end on an earlier note, the question does not diminish our conviction that the thought is in principle there.

* (This by Gregory Bateson, Mind and Nature, is helpful: " All receipt of information is necessarily the receipt of news of difference, and all perception of difference is limited by threshold. Differences that are too slight or too slowly presented are not perceivable. They are not food for perception. It follows that what we, as scientists, can perceive is always limited by threshold. That is, what is subliminal will not be grist for our mill. Knowledge at any given moment will be a function of the thresholds of our available means of perception. " My point is that expertise in forms of consciousness alters the threshold of perception.)

Home